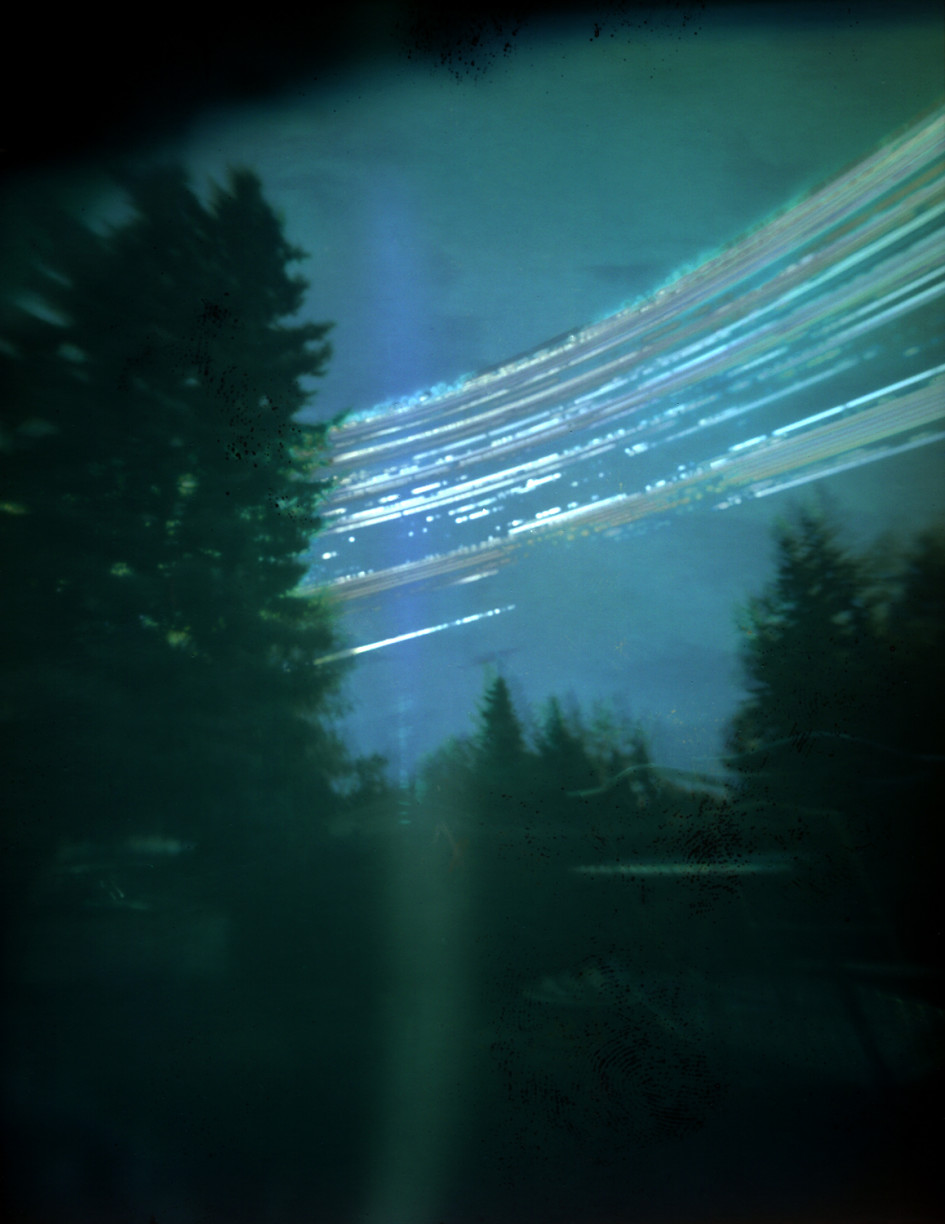

After a long time off from blogging, I’m returning to share a photograph that literally took the entire summer to make. Taken from outside my porch window, this image captures everything outside from June 21st to September 21st – encapsulating 3 months and, save for one day, the entire summer in a single image.

The broken lines in the sky that resemble Saturn’s well-known rings are nothing more than the sun’s path through the sky recorded for a quarter of the year. The breaks in the lines, resembling patterns of morse code, stand as a visual record of one of Alaska’s worst fire seasons and the welcomed rain that followed, both elements that obscured the sun’s light for days and weeks at a time. Throughout the scene, elements are faded and ghosted as a patio chair was moved and a neighbor’s truck moved after weeks of remaining in the same place. The bright glare in the middle of the image is a growing Delphinium that constantly whipped in the wind throughout the entire summer, never staying long enough in one place to be recorded clearly.

Although Solargraphs are nothing new, this is the first one I have done. A lazy solstice weekend three months ago led me to create three pinhole cameras out of empty cigar boxes my wife had been gifted. After some testing with short, 30-second exposures, I was only certain one would work well. Loaded and anchored down by several stones so that the box wouldn’t shift during its three months outdoors, I started the exposure.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

The darkroom has always seemed magical to me – and with each passing semester at UAF, I can attest to the fact that novice photographers, even in our digital age, are still as entranced by the process as I was nearly two decades ago. That said, in 20 years, I’ve seen my fair share of prints go through the developer and although the process of making traditional silver gelatin prints still does seem magical, I’ve replaced much of that magic with reasonable expectations and predictability.

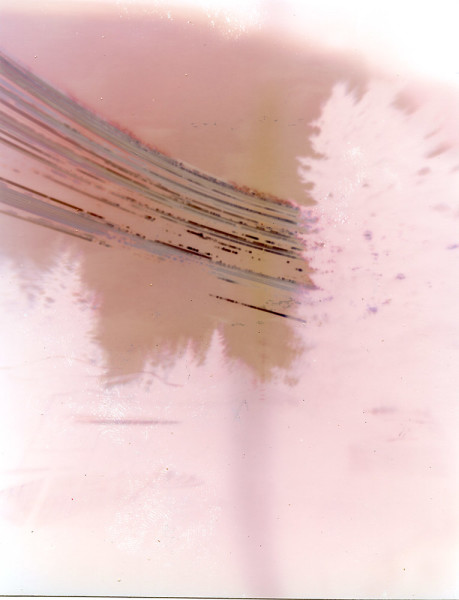

Solargraphs, however, are a welcomed infusion of magic in what has become predictable alchemy. Unlike traditional 30-second pinhole photographs that capture a latent image that is only revealed by the development process, Solargraphs are exposed so long that they burn an image into the paper, making what is traditionally hidden visible without the aid of chemistry. Surprisingly, as well, Solargraphs capture color on paper reserved for only black and white prints. Admittedly dulled, it’s still easy enough to pick up hues of blue, red, green and brown in these images.

Modern-day Solargraphs bring photography full circle with its most basic roots. Not only is the image created with the most basic camera (a darkened box with a pinprick of a hole) but it requires lengthy exposures that would even make Niépce cringe. Niépce’s first permanent photographic image took 8 hours to expose – mine took well over 2000 hours. Unlike Niépce’s image, mine is still entirely fugitive – meaning that, with time and continued exposure to light, my image will continue to expose and, eventually, fade away completely. This image, in many ways, is connected to photography as it existed before it’s official announcement in 1839 – before images could be “fixed”, rendered safe and non-reactive. Only visible under the dull light of the darkroom, the solargraph’s negative is a fragile element much like the early photographic records observed in dim candlelight.

Although not part of an ongoing series, this image represents part of my new approach to photographic art – challenging myself to broaden my horizons and learn something new with each passing month. I made a lot of amazing work this summer, all while this single image was being exposed – work I’ll hopefully start sharing in the days to come!

Leave a Reply