Eight and a half years ago, I sat in my vehicle staring at a stark landscape overlooking the Cook Inlet on a dreary and bone-chilling December day. I didn’t have a clue why this landscape drew me in, as I had claimed for years that I was not, nor would ever be, an “Alaskana” photographer, smitten with grand landscapes, wildlife photos and auroras. Something was different with this landscape, though: the overcast, grey skies flattened the light, creating abstract, stacked layers, while muted hues seemed to quiet the frigid winds. Far from “grand”, something deeper seemed to be speaking to me through this landscape.

My wife, sitting next to me, encouraged me to get out and take my camera with me. I hesitated, not only knowing that I was asking for my wife and six-year-old son to wait in a cold car for me to photograph, but to photograph a landscape — something I had no interest in. I reluctantly opened the door, spent 10-15 minutes roaming the dunes trying to find a composition, snapped a few, and, content, hopped back in the car and thought little of it. Over the next few days, I kept staring at the image, sharing it over and over again with my wife, convinced there was something there, but unable to speak about what it was.

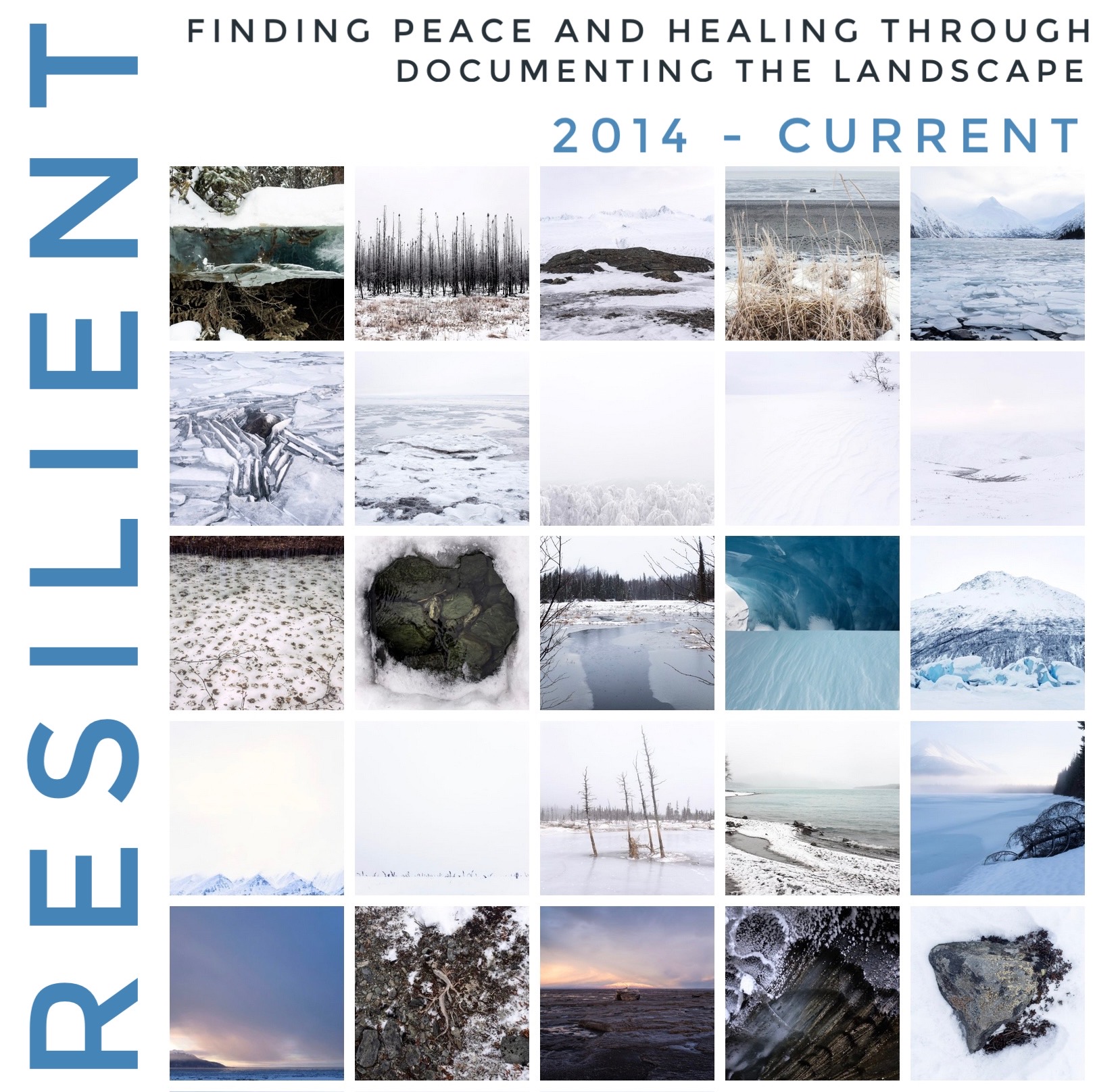

Initially, this exploration encouraged me to seek out similar stark compositions during the winter months, often relying on lengthy roadtrips throughout the state to find them. Dismal, gray, and overcast conditions provided uniformity in the skies, lonely stretches of rural highway eliminated the manmade presence in the landscape, and the limited color palette and square format sufficiently ignored landscape traditions. A project was starting to take shape, one that saw the strength, resolve, and resilience of the people of Alaska within these somber landscapes. What was captured, however, were more like portraits of her people, as Alaskans are, in many ways, a product of our home and our defining characteristics, both positive and negative, are reflected in the landscape.

What I didn’t realize until years later was how much this work was a reflection of various mental health struggles and a much-needed outlet to discuss it safely and non-verbally.

Even though I’ve known this to be true for several years, it’s still difficult to see those words written out. Societal and generational expectations being what they are, depression, anxiety, and mental health were, in general, things that I had been expected to cope with silently and privately. I had graduated with my MFA in 2014 and had fallen back into the bad habit of hanging up my camera for the winter. Without school to provide structure for my creativity, I eliminated my only creative outlet from October until May each year. As well, several hopes and dreams that had been my focus for years started fading and because I couldn’t find my way out of this self-imposed maze, I grew bitter, angry and withdrawn. Alaska’s isolation, its frigid cold, and endless dark all stood as constant reminders of this failure. Slowly, I fell out of love with my first true home as I was convinced Alaska was the reason I had failed at bringing those dreams to fruition. I felt lost, listless, and stranded.

What the project eventually called “Resilient” would do is break me of those destructive habits, encouraging me to create and find beauty in the bleakest part of the year. The work captured a rarefied Alaska, one that resembled the place we call home because it celebrated the simplistic and stoic beauty of the commonplace rather than only being in awe of her when she’s at her grandest. These images reflected and celebrated the characteristics of the people I held dear, called family, and loved for their uniquely Alaskan quirk. After a couple years traveling thousands of miles of lonely highways, seeking out reflections of Alaskans within the landscape, I not only started to enjoy creating in the bitter cold but also found myself falling back in love with the place I called home, deeper than ever before. For the first time in my 25+ years living here, I actually started looking forward to the winters because they healed me. Isolated stretches of highway provided much-needed contemplation and personal reflection. An ever-evolving formal design added incredible challenge to the photographic hunt, meaning some trips were considered successful with only two or three shots over 800 miles. As much as I was finding reflections of Alaskans in the landscape, I started to see my own self in these images, as well.

Only recently has this last revelation become not just present, but dominant. Reflecting back on my eight years with “Resilient”, I recognize that I was capturing my own mental state – fragile, struggling, cold, withdrawn, isolated, lost – using the land as a visual metaphor. Much more surprising, however, is the most recent realization that this was done as a collaboration: the land gave me grounding, purpose, expression, goals, focus, and a non-verbal vocabulary that I could lean on hard when I struggled. This entire project has been done in collaboration: isolated as it may seem, at its core, “Resilient” is a conversation between my first true home and myself.

One major lesson I took out of the pursuit of my master’s degree was that your art may speak to you differently than it does your audience — and that your relationship to the work can (and perhaps should) be different than the message you provide your viewer. Folks may look at these landscapes and appreciate them merely for the commonplace beauty they intend to encapsulate. I hope they see the personification and reflection of treasured Alaskan attitudes and characteristics in its landscapes. For me, however, this has been a collaborative project and conversation with the landscape that has led to a great deal of healing. Although pastels have only recently started to creep their way into the design of this broadening project, they have started to replace the traditionally somber, blue-toned images of ice and snow. If that’s not progress toward healing, I don’t know what is.

Currently, “Resilient” is represented by over 40 images, which can all be seen here.

Interested in purchasing prints from Resilient? Click here.

+There are no comments

Add yours