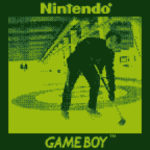

After purchasing five retro, low resolution Gameboy Cameras over the past four years, buying a homebrewed SD Card reader to transfer files, and hauling two Gameboys in my carry-on bag since 2020, I’ve been wondering what in the world I was going to use them for. Full of kitsch and hipster “retro-is-the-new-cool “mentality, these tiny, 0.014 megapixel wonders from the late 1990s attract a lot of interest among photographers and gamers, but few take more than a couple dozen photos before they’re relegated to a dusty shelf and life as a conversation piece, at best.

So how could I take my personal passion for retro video games and a ’90s, pixelated aesthetic and create a body of work that was personally meaningful, substantial and concept-driven? While I’m unsure that I have found the exact recipe yet, I’m excited to share what I’ve been working on thus far. If nothing else, this exercise in writing about the work might make it more obvious if I need to keep on refining what I’ve got or move on.

Learning to see with your chosen photographic format, film, camera or lens is one of the most important, establishing lessons for any photographer. While seeing in black and white is important to see value over hue and essential to a good composition, seeing in 2-bit has been a surprisingly difficult lesson for me. Seeing pixelated is easy enough, but rendering subjects with no more than shape and four “colors” has been a challenging transition as it’s surprisingly difficult to find the right combination of direct light, ambient luminance, and shadow to provide appropriate detail to effectively “see” subjects in pixelated renderings. There’s also the matter of appropriate viewing distance to allow our brains to render pixels as objects, people, and landscapes. The Gameboy screen works great because it’s small enough to allow us to mentally render the dots and subject – but it’s far too small for display in a gallery. Go too big, say wall-sized, and your audience is pressed upon the opposite wall failing to see what all those squares are supposed to be. Similarly, the camera was made as a portrait camera – it’s wide lens makes landscapes impossible without walking up to the subject.

A suitable challenge for me, I think. I’ve enjoyed these limitations because with them the Gameboy Camera isn’t just another camera that replicates the same picture I’ve already taken, except with a slightly different lens, film stock, or format. From the foundation up, the images I take with it require me to be a completely different shooter – I like that.

After ordering the Bitboy SD Card Reader for Gameboy in 2020, I started trying to figure out what I could do with this charming little bit of toy tech. Covid necessitated me to rely on still life or landscape and I quickly started playing with the images as a way to record my summer adventures with Aidan much in the same way some photographers shoot with a disposable film camera.

These early captures reminded me of an old, pixelated portrait I had taken of myself in 1986/87 or so at a pop-up studio in Wal-mart: it was digitally captured (though with what technology I don’t know) and printed on a dot-matrix printer. I always treasured that portrait of me more than any others because it was so different and foreign. Looking back at those years of my life, I started to see correlations in how I recall those memories and how the Gameboy records – the general idea is there, the shape of the event, but the significance it held at the time, the thoughts going through my head, are all lost to time. As I’ve gotten older, I’m keenly aware of how a lack of focus, anxiety, and depression factors into how present I am in life and all of its memorable events. I’ve tried to remember to put down my cameras and take in the moment more as I get older, hoping to internalize more crucial details of these memorable events.

The more that I thought about this connection with our recorded photographic memories, the more I wanted to travel with the camera and, like those images of the past, record travelogue photos with it. Even though travelogues weren’t as popular when I was growing up, travel necessitated the obligatory assemblage of a coffee table photo book where all your 3x5s and 4x6s could live for at least a couple decades in its sticky, acidic pages. Culturally, we collected photographs, taking our own, purchasing postcards, and, oddly enough, almost religiously relegating them to a newly-procured shoebox to stuff in the attic to be ignored, forgotten and neglected for a couple decades. What does it say about us and our memories when we treasure the act of recording them, only to lock them away until they’ve obtained a level of obscurity and anonymity? Why are we compelled to remember, only to immediately bury those memories?

Studies out there suggest that our smartphone picture obsession is fundamentally changing how we record and recall memories. Focused on obtaining the perfect picture that echoes the quality of the postcards available in the obligatory gift shop, we take ourselves out of the moment in a vain attempt to record something special. “Chimping”, the act of repeatedly reviewing our digital cameras, whether dSLR or iPhones, further takes us out of this moment. Places and our travel buddies become objects, still-lifes, and subjects, trivial in respect to the day’s tasks and little more than background noise. I often lament about the arrogance behind influencer photography, the fake awe of nature as a transaction for likes and followers, but aren’t we all guilty of this? Even when we don’t share our photographs online and merely relegate them to a shoe box, when we pull them out and share them with our descendants, aren’t we all hoping for a little envy, a little respect, and a little more social currency?

What the Gameboy does well is that it speeds this deconstruction of our memories, condensing decades of stories retold and manipulated, details overlooked and lost, memories replaced with more favorable ones, and it presents our present as imperfect. It reminds us of our own important task: to be present and to remember better. To recognize that any rendering requires your own participation to build it up into a picture-perfect memory. Perhaps even more important: it encourages us to put down our cameras and live.

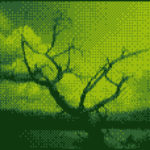

Initially, I only had interest in colorizing the images to mimic the original Gameboy screen, with its sickly shade of green. These files are exported to the SD Card (which functions as a “fake” printer) as black and white, 2-bit Bitmap images, measuring 128×112 pixels in size. Adding the green back into these images is done through a Photoshop action shared on the web, though I quickly realized many images I took lacked context without the appropriate colors. Early attempts merely altered the gradient of colors, but I was soon creating meticulously-drawn selections of individual subjects and using the action on parts of the image. This act echoed the idea expressed above: it recognized that any picture needed my own participation, my own coloring of those memories, to build it into a more perfect rendering. Through selectively editing my 2-bit image, I was adding details that made it more solidly 8-bit, perhaps even 16-bit.

What’s more was that I was able to imbue the images with the hues of my memories of visiting these places even if they weren’t represented in reality. With rich, saturated hues I could see the joy and happiness in my memories in ways that weren’t qualitatively defined in my reality-focused digital and film captures.

I’d like to also point out at this time that I’ve definitely spent more time in Photoshop with any of these derezzed, selectively-colorized captures than I do with any images captured by my 26 megapixel X-Pro 3. I think that’s pretty funny.

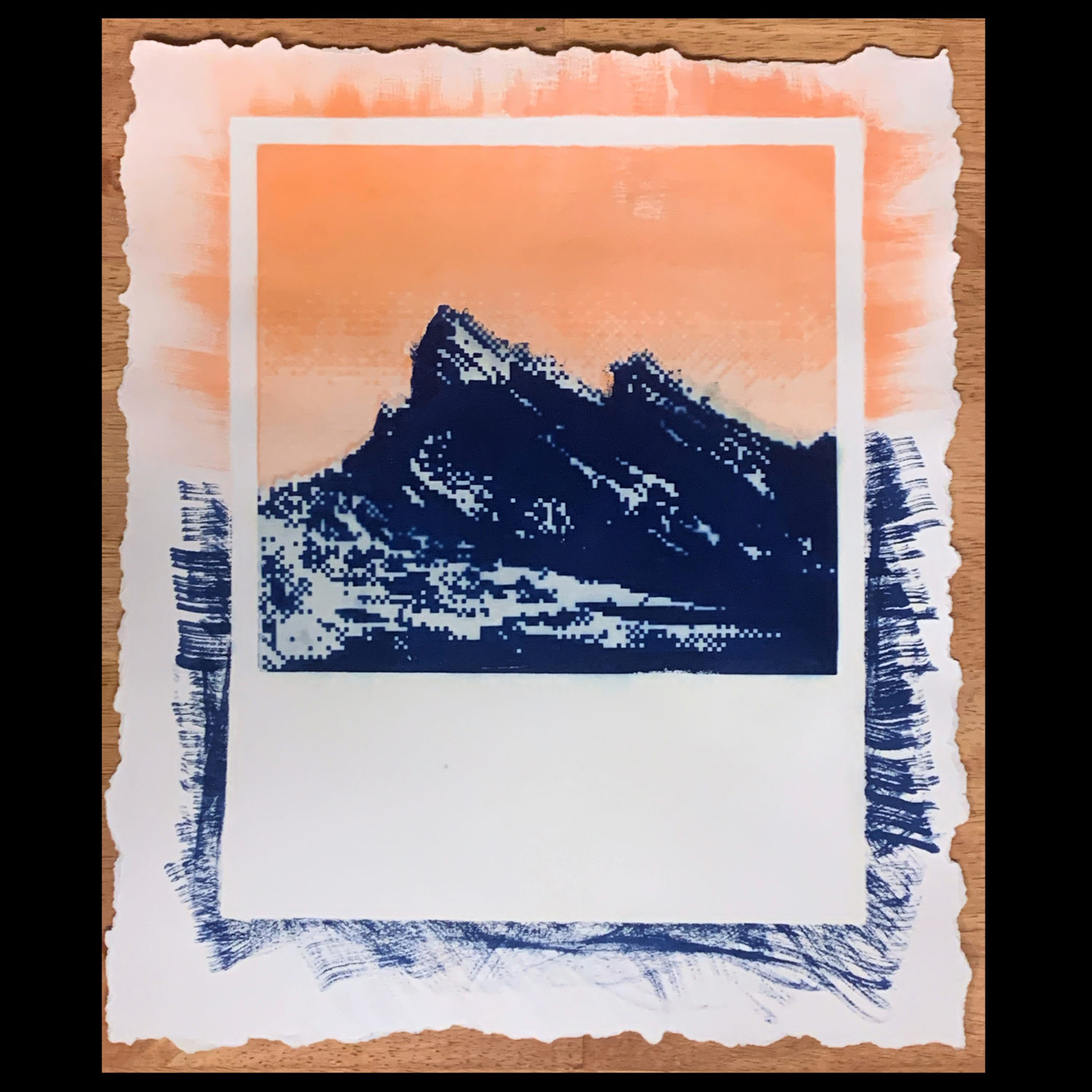

After this, I started playing around with adding borders to the images to suggest a Polaroid aesthetic, a film format that was marketed and sold as the perfect way to capture ephemeral moments before they disappeared. I’ve also digitally printed, framed, and entered my image of Vasquez Rocks in a local art exhibition. While the image wasn’t selected (nor does that prove or mean anything), I’m not certain this treatment of the image is appropriate. Right now, I’m sussing out a couple of things: mainly, whether this series should be printed digitally, should echo the Polaroid aesthetic (or is this too many translations, is this too kitschy?) and whether the image deserves further translation. After all, I’m already reinterpreting the memory through selective and emotive colorization. If this process is necessary to reconstitute the memory, wouldn’t retranslating it as an alternative process image suggest uplifting the kitsch of the snapshot to fine art, therefore imbuing it with the importance we often place in our memories? Piecing together and retranslating this image is only possible because I took in the scene, put down my camera, and experienced it – internalized it.

![]()

The above image only represents my first bit of dabbling into retranslating these digitally-altered, pixelated memories into a tangible, hand-created print. I’m unsure if this is the direction I want to go, but I am encouraged by the results. Right now, I’m selectively coating paper with Cyanotype Solution and Solarfast in an attempt to create multi-colored alt-pro prints. The more I explore these options, the more I realize that either printmaking processes or gum bichromate might serve my goals better, although both processes would require me to learn new mediums and processes. Although weary of that prospect (my own explorations into self-instruction with gum were.. ahem… bad), I would love for my work to force me out of my comfortable processes. Perhaps it’s time to enroll in some classes or workshops!

I’d love to know your thoughts on this process, on its concept, if this is exciting, interesting, concerning, or just plain dull. Folks seem to react well to the images, but they don’t pan out well on social media. I know, I know – that doesn’t mean anything. It’s just one of a myriad of metrics that I consider when gauging the success of work. Your input, if you actually read all 1700+ words of this, would be greatly appreciated.

+There are no comments

Add yours